new york

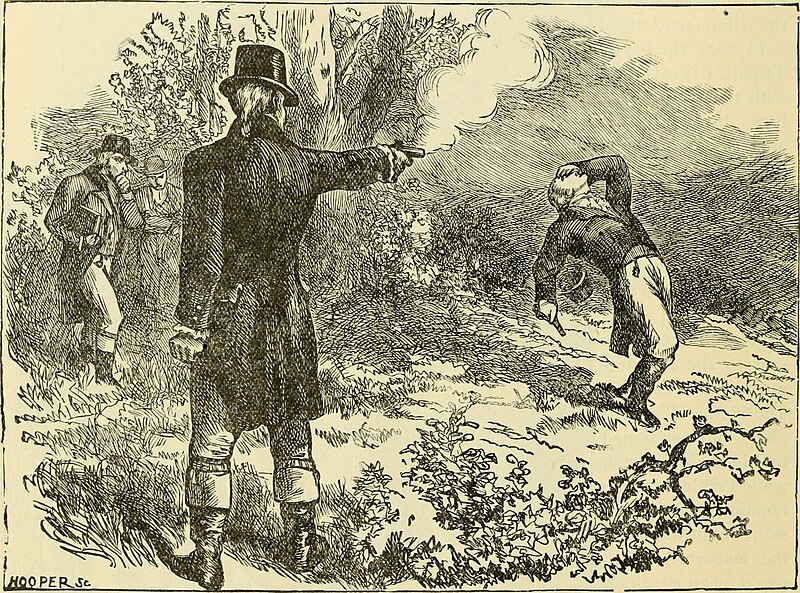

Throwback Thursday: Burr-Hamilton Duel 1804

Two-hundred, fifteen years ago, today, Vice President Aaron Burr shot former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in a duel in Weehawken, New Jersey.

At dawn on the morning of July 11, […] political antagonists, and personal enemies, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr met on the heights of Weehawken […], to settle their longstanding differences with a duel. The participants fired their pistols in close succession. Burr’s shot met its target immediately, fatally wounding Hamilton and leading to his death the following day. Burr escaped unharmed. This tragically extreme incident reflected the depth of animosity aroused by the first emergence of the nation’s political party system. Both men were political leaders in New York: Burr, a prominent Republican, and Hamilton, leader of the opposing Federalist Party. Burr had found himself the brunt of Hamilton’s political maneuvering on several occasions, including the unusual presidential election of 1800, in which vice-presidential candidate Burr almost defeated his running mate, presidential candidate Thomas Jefferson. In 1804, Hamilton opposed Burr’s closely fought bid for governor of New York. On the heels of this narrow defeat, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel on the grounds that Hamilton had publicly maligned his character.

[Source]

wikipedia.org & flickr.com

Alexander Hamilton, the chief architect of America’s political economy, was born on the Caribbean island of Nevis [and] came to the American colonies in 1773 as a poor immigrant. (There is some controversy as to the year of his birth, but it was either 1755 or 1757.) In 1776, he joined the Continental Army in the American Revolution and his […] remarkable intelligence brought him to the attention of General George Washington. Aaron Burr, born into a prestigious New Jersey family in 1756, was also intellectually gifted and [..] graduated from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) at the age of 17. He joined the Continental Army in 1775 […]. In 1790, he defeated Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law in a race for the U.S. Senate. Hamilton came to detest Burr, whom he regarded as a dangerous opportunist, and […] often spoke ill of him.

In the 1800 election, Jefferson and Burr became running mates […]. Under the electoral procedure then prevailing, president and vice president were voted for, separately. […] the candidate who received the most votes was elected president, and the second in line, vice president. What at first seemed but an electoral technicality […] developed into a major constitutional crisis when Federalists in the lame-duck Congress threw their support behind Burr. After a remarkable 35 tie votes, a small group of Federalists changed sides and voted in Jefferson’s favor. Alexander Hamilton, who had supported Jefferson as the lesser of two evils, was instrumental in breaking the deadlock.

[Source]

The duel was fought at a time when the practice was being outlawed in the northern United States and it had immense political ramifications. Burr survived the duel and was indicted for murder in both New York and New Jersey, though these charges were later either dismissed or resulted in acquittal. The harsh criticism and animosity directed toward him following the duel brought an end to his political career. The Federalist Party was already weakened by the defeat of John Adams in the presidential election of 1800 and was further weakened by Hamilton’s death.

[Burr] spent [many] years in Europe. He finally returned to New York City in 1812, where he resumed his law practice and spent the remainder of his life in relative obscurity.

[Source]

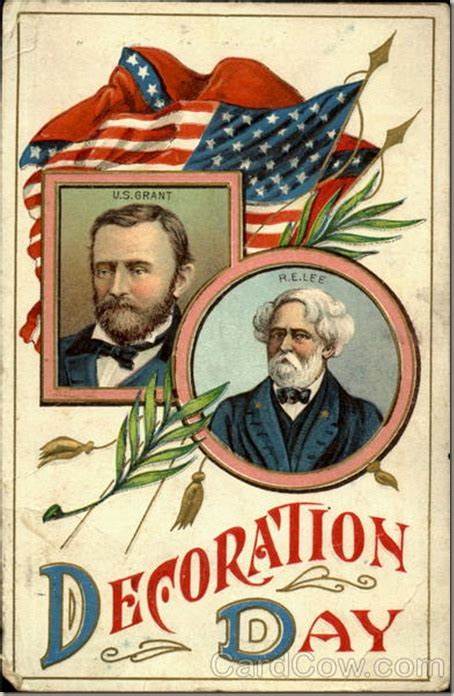

Throwback Thursday: Memorial Day

Memorial Day, as celebrated, has come and gone. The weekend BBQs and party gatherings are over. Some folks have returned to work after their Monday off while others took the entire week off and, possibly, headed to the beach to herald the “summer season”. I am posting, today, because from 1868 to 1970, Memorial Day was observed on May 30.

Our American Memorial Day has quite a rich, lengthy history and one that has its own area of research. Columbus State University in Georgia has a Center For Memorial Day Research and the University of Mississippi in Oxford has The Center For Civil War Research that covers Memorial Day in their data.

So, what IS the origin of our Memorial Day? That’s a good question and the following took two days to research.

May we remember them, ALL. ~Vic

Warrenton, Virginia 1861

A newspaper article from the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1906 reflects Warrenton‘s claims that the first Confederate Memorial Day was June 3, 1861…the location of the first Civil War soldier’s grave ever to be decorated.

Arlington Heights, Virginia 1862

On April 16, 1862, some ladies and a chaplain from Michigan […] proposed gathering some flowers and laying them on the graves of the Michigan soldiers that day. They did so and the next year, they decorated the same graves.

Savannah, Georgia 1862

Women in Savannah decorated soldiers’ graves on July 21, 1862 according the the Savannah Republican.

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania 1863

The November 19, 1863, cemetery dedication at Gettysburg was a ceremony of commemoration at the graves of dead soldiers. Some have, therefore, claimed that President Abraham Lincoln was the founder of Memorial Day.

Boalsburg, Pennsylvania 1864

On July 4, 1864, ladies decorated soldiers’ graves according to local historians in Boalsburg. Boalsburg promotes itself as the birthplace of Memorial Day.

Knoxville, Tennessee 1865

The first decoration of the graves of Union soldiers of which there is any record was witnessed by Surgeon Fred W. Byers, of the [96th] Illinois volunteer infantry, now surgeon general of the National Guard of the State of Wisconsin (Spring 1865).

Jackson, Mississippi 1865

The incident in Mrs. [Sue Landon Adams] Vaughan’s life, which assured her name a permanent place in history, occurred at Jackson […] when she founded Decoration Day by first decorating the graves of Confederate and Federal soldiers alike, in a Jackson cemetery on April 26, 1865.

Kingston, Georgia 1865

An historic road-side marker indicates Kingston as the location of the “First Decoration, or Memorial Day” (Late April 1865).

Charleston, South Carolina 1865

On May 1, 1865, in Charleston, recently freed African-Americans reburied Union soldiers originally buried in a mass grave in a Confederate prison camp. The event was reported in Charleston and northern newspapers and, some historians today cite it as “the first Decoration Day.”

Columbus, Mississippi 1866

Thus was established a custom which has become national in its adoption – Decoration Day – having its origin with the ladies of Columbus. Columbus also claims the distinction of being the first to decorate the graves of both Confederate and Federal soldiers, alike (Friendship Cemetery April 25, 1866). [See the poem The Blue & The Gray by Francis Miles Finch}

Columbus, Georgia 1866

To the State of Georgia belongs the credit of having inaugurated what has since become the universal custom of decorating annually the graves of the heroic dead. The initial ceremonies which ushered Memorial Day into life were held in Linnwood Cemetery, at Columbus, on April 26, 1866.

Memphis, Tennessee 1866

Yesterday was the day appointed throughout the South as a day of sweet remembrance for our brothers who now sleep their last long sleep, the sleep of death. That day (the 26th day of April) has, and will be, set apart, annually, as a day to be commemorated by all the purely Southern people in the country, as that upon which we are to lay aside our usual vocations of life and, devote to the memory of our friends, brothers, husbands and sons, who have fallen in our late struggle for Southern independence.

Carbondale, Illinois 1866

A stone marker in Carbondale claims that place as the location of the first Decoration Day, honoring the Union soldiers buried there. General John A. Logan, who would later become commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, the largest of the Union veterans’ organizations, officiated at the ceremony (April 29, 1866).

Waterloo, New York 1866

On Saturday, May 5, 1866, the first complete observance of what is now known as Memorial Day was held in Waterloo. On May 26, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson designated an “official” birthplace of the holiday by signing the presidential proclamation naming Waterloo, New York, as the holder of the title.

Richmond, Virginia 1866

The anniversary of the death of Stonewall Jackson was observed to-day by floral decorations of the graves of Confederate soldiers at Hollywood and Oakwood (May 10, 1866).

May 3, 1866 [they] formed the Ladies’ Hollywood Memorial Association, with the immediate aim of caring for and commemorating the graves of Confederate soldiers. All disposed to co-operate with us will repair, in such groups and at such hours as may be convenient, on Thursday, May 31st, 1866, to Hollywood Cemetery, to mark, by every appropriate means in our power, our sense of the heroic services and sacrifices of those who were dear to us in life and we honored in death.

Petersburg, Virginia 1866

It was in May of this year, 1866, that we inaugurated, in Petersburg, the custom, now universal, of decorating the graves of those who fell in the Civil War. Our intention was simply to lay a token of our gratitude and affection upon the graves of the brave citizens who fell June 9, 1864, in defence of Petersburg…

Southern Appalachian Decoration Day

From The Bitter Southerner:

Dinner on the grounds is not a phrase I hear these days. Just reading the phrase takes me back to those times with my grandmother at her church on […] Decoration Day Sunday. I grew up in north Alabama in the 1960s. Dinner on the grounds was a special occasion that followed the work of cleaning up the graveyard and placing fresh flowers beside the headstones. It provided a time to remember and celebrate the lives of the dear departed. ~Betsy Sanders

Today, we are here to eat, remember and bask in the Southern fascination of death […]. It’s Decoration Day. The South claims death with as much loyalty as we claim our children. J.T. Lowery, a former pastor […] misses when Decoration Day meant keeping company with headstones during dinner on the ground. Opal Flannigan is depending on women […] to uphold a tradition so old it’s hard to say when it emerged. German and Scots-Irish immigrants who birthed much of the Southern Appalachia’s culture in Virginia, Tennessee and the Carolinas likely brought these traditions [with them]. ~Jennifer Crossley Howard

From UNC Press Blog:

Many rural community cemeteries in western North Carolina hold “decorations.” A decoration is a religious service in the cemetery when people decorate graves to pay respect to the dead. The group assembles at outdoor tables, sometime in an outdoor pavilion, for the ritual “dinner on the ground.” There are variations of this pattern but, the overall pattern is fairly consistent.

Nationwide Observance 1868

In 1866, veterans of the Union army formed the beginnings of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization designed expressly to provide aid, comfort and political advocacy for veterans’ issues in post-war America. In 1868, the leadership of the G. A. R. sought through the following order to have the various local and regional observances of decorating soldier graves made into something like a national tradition.

Headquarters Grand Army Of The Republic

Adjutant-General’s Office, 446 Fourteenth St.

Washington, D. C., May 5, 1868.

General Orders No. 11.

From The History Channel:

By proclamation of General John A. Logan of the Grand Army of the Republic, the first major Memorial Day observance is held to honor those who died “in defense of their country during the late rebellion.” Known to some as “Decoration Day,” mourners honored the Civil War dead by decorating their graves with flowers. On the first Decoration Day, General James Garfield made a speech at Arlington National Cemetery, after which 5,000 participants helped to decorate the graves of the more than 20,000 Union and Confederate soldiers buried in the cemetery.

The 1868 celebration was inspired by local observances that had taken place in various locations in the three years since the end of the Civil War. In fact, several cities claim to be the birthplace of Memorial Day, including Columbus, Mississippi; Macon, Georgia; Richmond, Virginia; Boalsburg, Pennsylvania; and Carbondale, Illinois. In 1966, the federal government, under the direction of President Lyndon B. Johnson, declared Waterloo, New York, the official birthplace of Memorial Day. They chose Waterloo, which had first celebrated the day on May 5, 1866, because the town had made Memorial Day an annual, community-wide event, during which businesses closed and, residents decorated the graves of soldiers with flowers and flags.

By the late 19th century, many communities across the country had begun to celebrate Memorial Day and, after World War I, observers began to honor the dead of all of America’s wars. In 1971, Congress declared Memorial Day a national holiday to be celebrated the last Monday in May. Today, Memorial Day is celebrated at Arlington National Cemetery with a ceremony in which a small American flag is placed on each grave. It is customary for the president or vice president to give a speech honoring the contributions of the dead and to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. More than 5,000 people attend the ceremony annually. Several Southern states continue to set aside a special day for honoring the Confederate dead, which is usually called Confederate Memorial Day.

Throwback Thursday: Hour Glass 1946

Seventy-three years, ago, today, the long forgotten variety show Hour Glass debuted on NBC. It was the first hour-long musical/skit/comedy in television history. Co-hosts were Helen Parrish and Eddie Mayehoff. Edgar Bergen appeared on November 14 performing his ventriloquism, a rare thing for radio personalities. He later became host of the program.

From Wikipedia

Hour Glass was sponsored by Standard Brands, promoting Chase and Sanborn Coffee and, Tenderleaf Tea. The program included comedians, musicians, entertaining films (such as a film of dance in South America) and a long, live commercial for the sponsor’s products. Such famous names as Doodles Weaver, Bert Lahr, Dennis Day, Jerry Colonna, Peggy Lee and Joe Besser appeared on the program.

The Columbia History of American Television attributed the program’s short life to its cost, saying, “Standard Brands invested $200,000 in this series over its ten-month tenure at a time when that level of investment just couldn’t be supported and sustained, leading to the Hour Glass’s abbreviated run.” Another factor was that James Petrillo, president of the American Federation of Musicians, forbade musicians from performing on television without an agreement between the AFM and the networks, thus, limiting directors, and performers, to use of recorded music.

From the Television Academy Foundation:

It is historically important, however, in that it exemplified the issues faced by networks, sponsors and advertising agencies in television’s formative years. The program was produced by the J. Walter Thompson agency […]. The lines of responsibility were not completely defined in those early years and the nine-month run of Hour Glass was punctuated by frequent squabbling among the principals. Each show was assembled by seven Thompson employees working in two teams, each putting together a show over two weeks in a frenzy of production. It must have been the curiosity factor that prompted some stars to appear on the show because they certainly were not paid much money. Hour Glass had a talent budget of only $350 a week, hardly more than scale for a handful of performers. Still, Standard Brands put an estimated $200,000 into the program’s nine-month run, by far the largest amount ever devoted to a sponsored show at that time. In February 1947, Standard Brands canceled Hour Glass. They were pleased with the show’s performance in terms of beverage sales and its overall quality, yet, were leery about continuing to pour money into a program that did not reach a large number of households (it is unclear if the show was broadcast anywhere other than NBC’s interconnected stations in New York and Philadelphia). The strain between NBC and Thompson played a role as well. Still, Hour Glass did provide Thompson with a valuable blueprint for the agency’s celebrated and long-running production, Kraft Television Theatre.

More information from Eyes of a Generation

Throwback Thursday: The Carolina Parakeet 1918

John James Audubon painting…1825

One hundred and one years ago, today, the last known Carolina Parakeet, a small, green, neotropical parrot native to the United States, died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo.

It was the only indigenous parrot to the Mid-Atlantic, Southeast & Midwest states. They ranged from southern New York, to the southern tip of Wisconsin, to Eastern Colorado, down to Central & Eastern Texas, across the Gulf of Mexico to the seaboard and all parts in-between. Also called a Carolina Conure (conuropsis carolinensis), they had a bright yellow head with a reddish-orange face and a pale beak.

From Audubon:

[…] lived in old forests along rivers. It is the only species classified in the genus Conuropsis. It was called puzzi la née (“head of yellow”) or pot pot chee by the Seminole and, kelinky in Chickasaw.

The last known wild specimen was killed in Okeechobee County, Florida, in 1904, and the last captive bird died at the Cincinnati Zoo on February 21, 1918. This was the male specimen, called “Incas”, who died within a year of his mate, “Lady Jane”. Coincidentally, Incas died in the same aviary cage in which the last Passenger Pigeon, “Martha“, had died nearly four years earlier. It was not until 1939, however, that it was determined that the Carolina Parakeet had become extinct. Some theorists at this time, though, believed a few may have been smuggled out of the country in mid 20th century and may have repopulated elsewhere, although the odds of this are extremely low. Additional reports of the bird were made in Okeechobee County, Florida, until the late 1920s, but these are not supported by specimens.

The Carolina Parakeet is believed to have died out because of a number of different threats. To make space for more agricultural land, large areas of forest were cut down, taking away its habitat. The bird’s colorful feathers (green body, yellow head and red around the bill) were in demand as decorations in ladies’ hats. The birds were also kept as pets and could be bred easily in captivity. However, little was done by owners to increase the population of tamed birds. Finally, they were killed in large numbers because farmers considered them a pest, although many farmers valued them for controlling invasive cockleburs. It has also been hypothesized that the introduced honeybee helped contribute to its extinction by taking many of the bird’s nesting sites.

A factor that contributed to their extinction was the unfortunate flocking behavior that led them to return immediately to a location where some of the birds had just been killed. This led to even more being shot by hunters as they gathered about the wounded and dead members of the flock.

This combination of factors extirpated the species from most of its range until the early years of the 20th century. However, the last populations were not much hunted for food or feathers, nor did the farmers in rural Florida consider them a pest, as the benefit of the birds’ love of cockleburs clearly outweighed the minor damage they did to the small-scale garden plots. The final extinction of the species is somewhat of a mystery but, the most likely cause seems to be that the birds succumbed to poultry disease, as suggested by the rapid disappearance of the last, small but, apparently healthy and reproducing flocks of these highly social birds. If this is true, the very fact that the Carolina Parakeet was finally tolerated to roam in the vicinity of human settlements proved its undoing. The fact remains, however, that persecution significantly reduced the bird’s population over many decades.

From Birds of North America:

A consumer of sandspurs, cockleburs, thistles, pine seeds and bald cypress balls, as well as fruits, buds and seeds of many other plant species, the Carolina Parakeet was evidently a fairly typical psittacid with catholic feeding habits, loud vocalizations and highly social tendencies. However, unlike many other parrots, it was clearly a species well adapted to survive cold winter weather. Although generally regarded with favor by early settlers, the parakeet was also known locally as a pest species in orchards and fields of grain and, was persecuted to some extent for crop depredations. Its vulnerability to shooting was universally acknowledged and was due to a strong tendency for flocks not to flee under fire but, to remain near wounded con-specifics that were calling in distress.

[…] there are no known ways to evaluate many issues in Carolina Parakeet biology except through extrapolations from the biology of closely related species and through reasoned interpretations of the fragmentary writings of observers who have long since passed from the scene. Fortunately, early naturalists prepared a few accounts with substantial amounts of useful information.

From All About Birds:

Outside of the breeding season the parakeet formed large, noisy flocks that fed on cultivated fruit, tore apart apples to get at the seeds and, ate corn and other grain crops. It was therefore considered a serious agricultural pest and was slaughtered in huge numbers by wrathful farmers. This killing, combined with forest destruction throughout the bird’s range and, hunting for its bright feathers to be used in the millinery trade, caused the Carolina Parakeet to begin declining in the 1800s. The bird was rarely reported outside Florida after 1860 and was considered extinct by the 1920s.

I had no idea that my area of the U.S. had a native parrot species. It is a crying shame that this beautiful, lively bird was driven to extinction. They were easily tamed and had long life spans. Perhaps, there are some still in existence and carefully hidden. ~Vic

Tune Tuesday: The Charleston 1924

Ninety-five years ago, today, (as best as I can tell) the #1 song playing was The Charleston. Composed by James P. Johnson with lyrics by Cecil Mack, it was originally featured in the Broadway musical Runnin’ Wild that premiered in New York on October 29, 1923. It was first recorded by Arthur Gibbs & His Gang and was released November 23, 1923.

This is some fancy foot work.

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2